Part of the music this coming Sunday morning will be the Te Deum in B-flat by Sir Charles Villiers Stanford (1852-1924). We rarely have the opportunity to hear a Te Deum at the cathedral these days as the 10:30am service is invariably a celebration of communion rather than Morning Prayer (Matins) with which the hymn is associated. However, given the trinitarian nature of its text a Te Deum is entirely appropriate for Trinity Sunday.

This particular setting has a long and storied history. Stanford wrote it in 1879 while organist and director of music at Trinity College, Cambridge. It is part of his Morning, Communion, and Evening Service in B-flat major, Opus 10 which consists of music for each of the principal Anglican services; last March the choir sang the Magnificat and Nunc Dimittis from this set as part of the evensong marking the 100th anniversary of Stanford’s death. The Te Deum was chosen as part of the music for the coronation of King Edward VII in 1902, for which Stanford orchestrated the original organ part and added the short introduction at the beginning; coincidentally(?) later in 1902 Stanford was knighted for his services to music. (Edward VII was the monarch who gave his name to Kingsway and King Edward Avenue in Vancouver; another piece commissioned for the coronation was Parry’s I Was Glad, heard at many a royal service since. And one attendee at the coronation in Westminster Abbey was Vancouver musician Frederick Dyke, who had been serving as choirmaster at Holy Rosary; his leave of absence was so long he lost that position, but instead took up similar duties at Christ Church.)

Stanford’s Te Deum in B-flat became a particular favourite at Christ Church; apart from “normal” services (as a ‘low church’ Morning Prayer was much more common in those days) it was performed as part of the inaugural recital on the new Hope-Jones organ in 1911, the service commemorating the silver jubilee of King George V in 1935, the service of dedication for the new Casavant organ in 1949, and the service marking the 1951 visit of Princess Elizabeth and Prince Philip, among other occasions. As far as we can tell the last time Stanford’s setting was heard at the cathedral was June 1978, so another outing is long overdue!

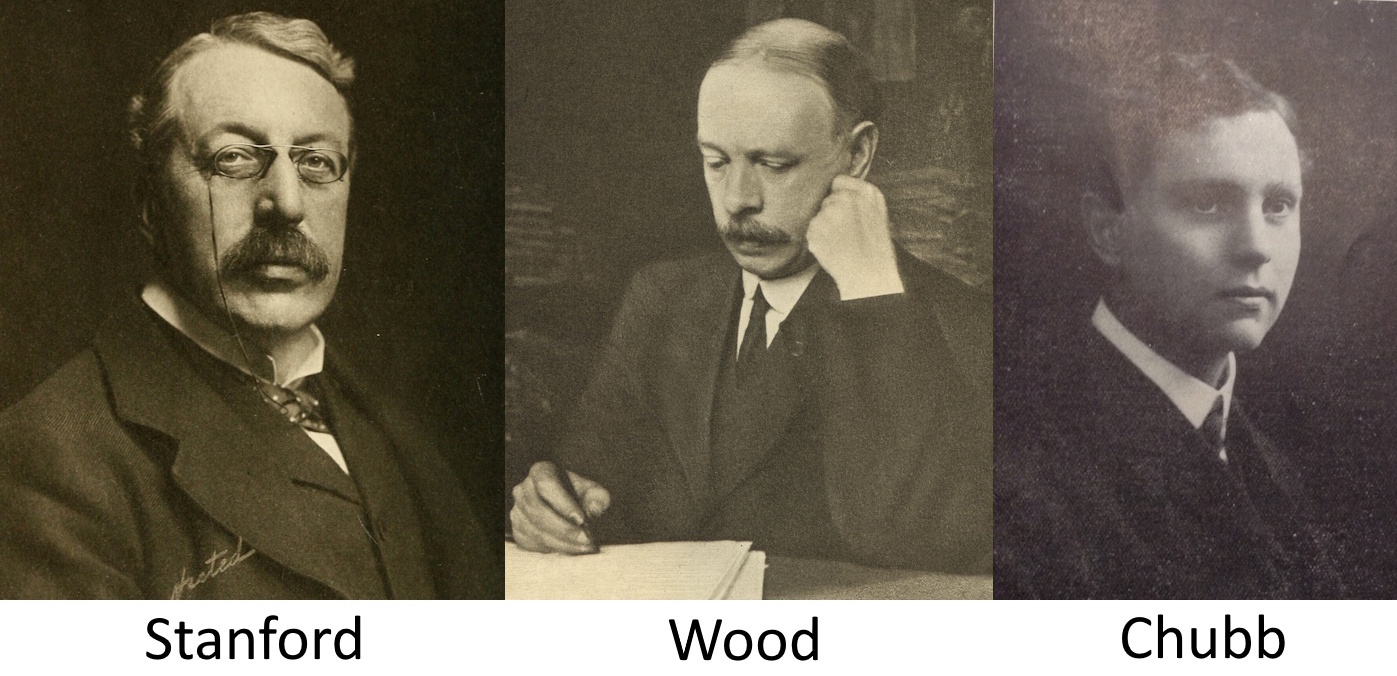

There is one further connection between Stanford and Christ Church – the cathedral’s long-serving (1912-1946) organist Frederick Chubb studied composition with Stanford at Cambridge University, along the way experiencing his teacher’s legendary temper: “Although Professor of Music, Stanford spent most of his time in London where he taught at the Royal College of Music, so that Fred’s contacts with him were relatively few. However, he did manage to irritate Stanford’s paper-thin skin over an incident which occurred at the end of a class just after Stanford had given the assignment for the next class, two weeks hence. It required writing a set of variations on a given theme. Stanford had not specified the number of variations he expected and Fred impetuously vocalized the inquiry, forgetting that Stanford regarded any question as an affront to his ability to make things clear. His irritation was expressed through the sarcastic reply that perhaps 200 variations might be enough, provided that Fred should be prepared to have 199 of them blue-pencilled! Though stung, Fred did in fact produce some 25 variations, a number far in excess of what was really expected and Stanford was somewhat taken aback. In fact, there might have been a touch of remorse, for some weeks later, in looking over the next assignment, a part-song, Stanford, after some scrutiny, suggested that Fred’s submission be put to one side for publication. This, from Stanford, was unheard of praise and meant much to Fred.” [From a Chubb family memoir at the Diocesan Archives]

Sir Charles Wood (1866-1926), the composer of our anthem during communion, had himself been a student of Stanford. Like him Wood was an Irishman but, unlike Standford, was shy and restrained. He studied at Selwyn College, Cambridge and began teaching there before moving on to Gonville and Caius College. Along with Stanford, Wood was one of the best composition teachers in England, numbering among his pupils Ralph Vaughan Williams, Herbert Howells, and Sir Thomas Beecham. Fred Chubb also took private lessons in composition from Wood, visiting his house every Tuesday morning for a period of three years. Wood eventually succeeded Stanford as Professor of Music at Cambridge in 1924. He produced two different settings of Oculi Omnium, one of which is a canon in four parts, reflecting Wood’s reputation as an unequalled teacher of counterpoint and fugue.